Those Eyes.

My grandmother’s eyes would light up with a girlish “what could I do?” expression and she’d say, “Oh, your grandfather was handsome!” But I knew that because I’d seen photographs.

My grandmother’s eyes would light up with a girlish “what could I do?” expression and she’d say, “Oh, your grandfather was handsome!” But I knew that because I’d seen photographs.

This is a draft of a song from my musical, Jack.

I haven’t decided for sure what her name will be — I keep going back and forth on this, but at the moment I’m pretty sure I’m going to change most of the names of characters based on real people — but this is sung by the grandmother to her grandson, Jack. (Picture Jack and his grandmother doing a little Garland/Astaire soft-shoe during that instrumental break.)

There are two kinds of people in this world: city people, and everyone else. Jack knew early on which one he was.

I’ve used lots of copyrighted images in this video, mostly without permission. These videos are my work sketches, sort of like mood boards, to help me visualize the songs, and meant only to be shared with friends. I don’t claim any rights to this work, except to the underlying song.

This summer is the 40th anniversary of my move to New York. I don’t remember the exact date, but it was August. I had planned to spend the summer before I moved here in Bloomington, Indiana, living with a high school friend and working to save what money I could, but after pounding the pavement for a week or so, and still no job, discouraged and sweaty, I went into the Indiana University library to cool off, picked up the New York Times to read, reflexively flipped to the “want ads,” and saw a tiny listing reading something like, “Counselors Wanted at boys’ camp in Upstate New York, Call the Fresh Air Fund, etc.” So I called.

They were looking to fill the position of “Nature Counselor” at the camp for boys ages 13-15. At that time, in addition to sending underprivileged (do they still use that word?) New York City kids to live for a week or two with rural families, the Fresh Air Fun also ran four summer camps near Fishkill, New York: one for disabled kids, one for girls, and two for boys (divided into ages 10-12 and 13-15, as I remember). Either they were desperate to fill the position (it was all very last-minute) or I bluffed well, but they offered me the job on the phone, on the spot. My minimal qualifications (I don’t know, an 8th grade leaf collection, a nature merit badge in Boy Scouts, just being from Indiana?) were more than enough. These kids had never seen a tree that wasn’t in a park.

Needless to say the experience was life-changing, not just the part about spending a summer in the woods with very poor, very street-savvy teenage boys who were not afraid of much but they were afraid of the dark, and the forest, and any noise they couldn’t identify, which there are a lot of in the dark in the forest. It was physically and emotionally exhausting work and the perfect preparation for my new life in New York.

Nearly every time I pass Port Authority to this day, I remember arriving there alone with a huge duffel bag and my dulcimer (because of course poor Black city boys are dying to learn “Go Tell Aunt Rhody” on a dulcimer). I’d been up all night, arrived on a Greyhound bus in the morning, and had to walk from there to an office somewhere in the far west of Hell’s Kitchen with all my stuff. When I stopped at a crosswalk about halfway there, my hand, the one that was carrying my dulcimer, went completely limp and I dropped the case. I had to wait for about 15 minutes till I got my grip back.

Pretty much everything about New York was terrifying and hard at first, and I was in heaven, knowing I had finally arrived home.

The cabins where we slept, one counselor with about 8 or 10 boys in each cablin. But since I was one of the specialty counselors, I got to sleep in a cabin with all adults.

The staff. I regret having no photos of the kids. They were insanely challenging boys but smart and hilarious, very observant, often insightful and affectionate.

So. A year ago last March, I was getting ready for a first table reading of the musical I’d been working on for a couple years. I had a date, a room, a cast, a draft. And then the world changed. I put my musical on the back burner and decided to begin writing a book because I had an idea I was excited about and I could write a book at home by myself.

In the last year, I’ve made great progress on the book. It’s big and gets bigger as it slowly takes shape in my mind and on the page. I’ve written about 150 manuscript pages and I’ve only dealt with less than 1/4 of the material. Now, I have a lot of research to do requiring travel to various towns and libraries and courthouses, and that should be possible before too long.

It occurred to me this week that another thing that will be possible before too long is a table reading of my new musical. So I’ve been listening to the songs and revising the script all week. The book and musical are not exactly the same story, but there’s significant overlap. I’ve changed names and fictionalized quite a bit in the play whereas the parts of the book that are autobiographical have not been altered — except in the way that one’s memory is always making revisions. So I decided to remove one thread of the story from the musical which is dealt with more directly in the book and which I struggled mightily to integrate into the musical, probably unnecessarily.

I wonder now if I’ve made a big mess of it, but that’s what table readings are for — to find out how big a mess you’ve made.

This song is sung by Augusta Cheney who is the sister of Horatio Alger, the nineteenth century writer of books for boys, who was lionized by 20th century conservatives for his “rags to riches” stories, all of them variations on a narrative established in his first book “Ragged Dick” of a homeless but smart and ambitious street kid who rises in the world through dumb luck and the mentorship of an older man who takes an interest in him. Alger’s first career as a minister was cut short when he, as the young pastor of a Unitarian church in Brewster Mass., was accused of sexually molesting boys in his congregation and run out of town. The church covered up the scandal, Alger moved to New York City, and he began his long literary career. In his will, he stipulated that his sister Augusta destroy all his personal papers, correspondence, and manuscripts, which she did. Modern historians consider this a great loss and Augusta Cheney somewhat of a villain. In this song, she defends herself.

This song came up in my shuffle on the plane on the way home from Indiana yesterday, after a visit — the first in a year and a half — with my sister and her husband and her three boys (my nephews, who are no longer boys but all young men now), my brother and his partner of nearly 30 years, my oldest dear friend Martha, and my dad who is 87, and that a capella coda that Carly Simon sings has been in my head ever since, the best kind of earworm.

In high school, I listened to this album over and over and over and, though I didn’t and still do not know what the song is about — something about the Pilgrims and an ex-lover and a voyage somewhere you’ve never been to but that is home? — I was moved by it and I am still. I’m sure back then my deep feelings were at least partly due to James Taylor’s eyes looking back at me from the album cover.

I still love this record best of all the James Taylor albums, and this song is my favorite among many favorites.

Like others I’m sure, as a kid I loved that James Taylor and Carly Simon were married. Shortly after I moved to New York, I saw him and their two children on the Upper West Side, all of them looking willowy and beautiful. And then a year or two later, they were divorced. I’ve long imagined their final argument:

Carly (at the end of her rope): And please stop pronouncing “the” like “thee.”

James: Why?

Carly: Because it’s irritating.

James (crestfallen): But it’s my thing.

Carly:

James:

It’s very hot today. New York has always had a reputation for miserable, muggy summers, but this is early for a string of 90° days.

On days like this I always remember that when we were young we didn’t have air conditioning in the city. No one I knew had it. It was miserable, but we tolerated it like so many other fucked up things in the city because it was the price of living here. We sat out on stoops in the evening and drank tall boys in paper bags. We ate cheap Mexican food on the sidewalk, went out dancing all night, to the movies in the afternoon when we were desperate to cool off for a couple hours. We slept naked on bare mattresses in front of windows with box fans rattling and blasting hot air across us all night long. We didn’t get much sleep. Now there are a thousand festivals of all kinds in the city all summer long and it’s crowded with tourists, but in the 1980s, the city emptied out in July and August when everybody who could afford it left for Fire Island, or the Hamptons, or Cape Cod or wherever they went, I don’t know I stayed. We had the place to ourselves, free of rich people.

I don’t know if this is true, but I always thought the reason we didn’t have air conditioners was because the electrical outlets in the tenement buildings we all lived in weren’t wired for it. But we couldn’t have afforded the higher utility bills all summer anyway, we lived so close to and usually over the edge of our means. I guess some time in the late 90s, they must have started making air conditioners that used regular voltage, who knows?, but I remember when my partner Jay and I went to the P.C. Richards on 14th St. and bought a cheap little window unit on an installment plan for our tiny street level studio apartment that we shared with four cats who were every bit as relieved as we were to feel that cool air. But we were just as broke as ever so we only turned it on when the temperature got into the 90s, which used to be pretty much limited to August.

Maybe I’m spoiled, maybe I’m fussier now that I’m older, maybe I’m having less fun to distract me (because summers in New York were if nothing else fun), but I can’t imagine living without a.c. now in the city. Or I can imagine which is why I know I would not tolerate it. Many of our older neighbors in the co-op, who bought their apartments in the 1950s and live on fixed incomes, have not installed air conditioners. They tough it out. On really hot days, they go to “cooling centers,” public spaces like schools and community rooms, where they hang out during the heat of the day. And, I imagine, go home at night to sleep naked in front of box fans rattling in their windows.

On this day in 2003, the Supreme Court ruled in Lawrence vs. Texas that state laws against homosexual sex were unconstitutional. I was 42 years old when it became legal for me to have sex in the United States of America. (I recommend the book Flagrant Conduct, about the Lawrence case. It’s a real page-turner.)

When I was born, 1961, “the infamous crime against nature” was a felony in every state. Over the next 42 years, a handful of states repealed their sodomy laws or reduced the penalties, but in 2003 same-sex sodomy was still a crime in 13 states, in some states still carrying long prison sentences and hard labor.

Lawrence vs. Texas reversed the 1986 S.C. ruling in Bowers vs. Hardwick which had upheld laws against gay sex. 1986. I was 25.

I place these events in my own timeline not to make it all about me, but to, 1, say that these are laws that shape lives, and 2, to convey how recent, and to my mind tenuous, is this so-called rapid shift in attitudes toward queer people that we keep hearing about. The Republican Party, as it exists today, doesn’t just want Roe vs. Wade reversed, not only are they gunning for the Voting Rights Act, they’re coming after all the 1950s and 60s civil rights laws, and the New Deal, and Obergefell (gay marriage) and Lawrence vs. Texas while they’re at it. (Sixteen states still have sodomy laws on the books which they still occasionally find sneaky ways to enforce, and which would go back into full effect if Lawrence were overturned.) For minorities whose ability to live their lives unmolested has so often depended on court rulings, the current religious conservative makeup of the Supreme Court is terrifying.

I don’t say all this to wallow in despair (though I struggle with my share of that lately) but to say that it’s a long war with an uncertain outcome. But that’s no reason not to keep fighting. In fact, it’s the reason TO keep fighting.

Of course Blue is one of my favorite albums but it sounds stupid to say that. Joni Mitchell’s Blue, which is 50 years old this week, exists somewhere outside of any trivial list I or anyone might make, any bestowing of a subjective distinction or rank.

When I hear it, or any of its songs, the thought is never far of the first time I heard it, or rather listened to it, with a boy named Richard in his dorm room at DePauw University, where I ended up one winter night my sophomore year of college when I was home for the Christmas break. I went to school in Oxford, Ohio at Miami University. DePauw was the small liberal arts college in the town where my family lived, where I’d gone to high school.

I had become friends with a piano student named Nancy, who was wildly funny and wildly talented and just wild, and somehow through her had met Richard, a soft-spoken boy with thick, dark hair and bright blue eyes, wearing a soft, expensive-looking yellow sweater, a vocal performance student in the music school, though no one I talk to now who was part of that group of friends remembers how we met Nancy, who is dead now so we can’t ask her, and they don’t remember Richard at all. A week or two into January, when I was back at school, Richard drove to Oxford to visit me. I don’t remember exactly what happened — I’ve probably pushed it out of my memory because I’m ashamed to have treated him, or anyone, so badly — but in Ohio everything felt different, or I should say I felt differently about Richard. He left brokenhearted.

But before all that, we were alone in his dorm room together very late one very cold night until very early, sitting on two chairs facing each other, his stocking feet between mine, listening to Blue. He knew every word, as I do now. Before that night I used to say, if anyone asked, that I didn’t care for Joni Mitchell because “all her songs sound alike.” I’m nearly as ashamed of that as I am of dumping Richard.

The Richard in The Last Time I Saw Richard is nothing like my gentle, effeminate college boy in the yellow sweater. But still.

The beginning of Pride season, combined with Sarah Schulman’s new book about ACT UP and my current writing/rabbit hole, had me thinking about Outweek. Life, for a few years there, revolved around Outweek, the magazine that kept us all up to date on the epidemic, queer life, ACT UP and Queer Nation and WHAM and all the other AIDS and queer activism, as well as arts and culture in fin de siècle plague-era New York. I can’t think of another example of any media that so shaped my life and world view. Everyone I knew devoured it every week.

I loved Outweek so much that this nasty little diatribe by a pseudonymous lesbian music “critic” about the very first version of what is now LIZZIE in 1990 didn’t put me off the magazine as much as it put me off pseudonymous lesbian music “critics.” And pseudonymous non-lesbian music “critics.”

This is probably self-evident, but it’s not a super great idea to send a letter to a magazine protesting a negative review. They will win. They have a magazine. (But the thing about Outweek is that it felt like our magazine, everybody’s magazine, and in many ways it was. The “Letters” section was long and probably the most read.)

Anyway, I should say that — though it retains its spirit and volume, the story, the core idea and some of the songs, its queerness and wild feminism, its reason for being — 1990’s Lizzie Borden: An American Musical is not 2021’s LIZZIE. It was 45 minutes long, started with the murders, and contained 4 songs. It was rough and some of the criticism in this review is legitimate. That was the beauty of the downtown experimental theater scene, that you could work stuff out on stage in front of a supportive audience that understood that creating serious, provocative, original work is a process. There would be no LIZZIE, in the full-length, narratively coherent, every beat completely thought through, professionalized form it takes today if we hadn’t had the freedom and support of that community.

I miss how wild you could be back then though. I miss the low commercial stakes that allowed artists to take crazy aesthetic risks.

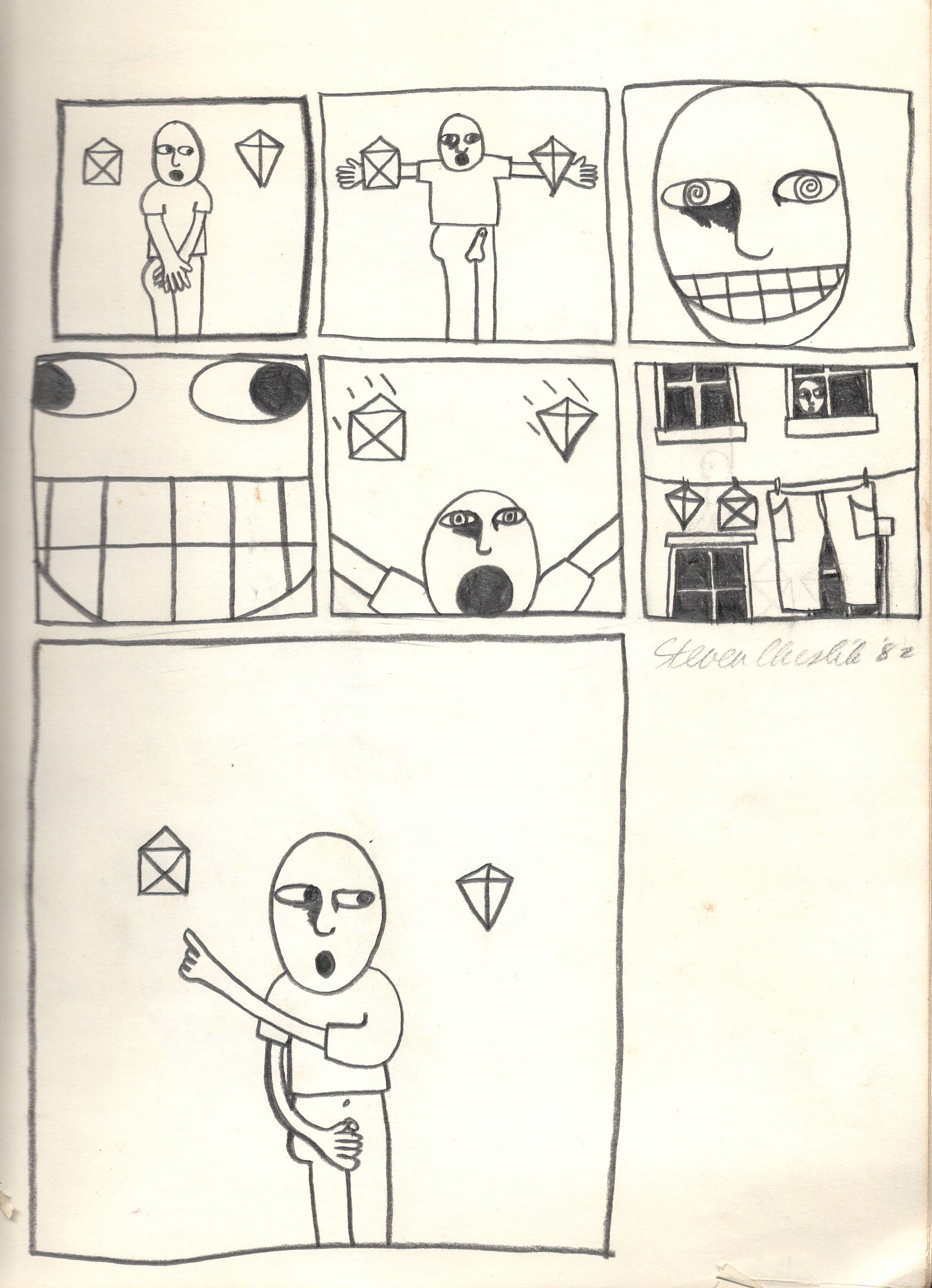

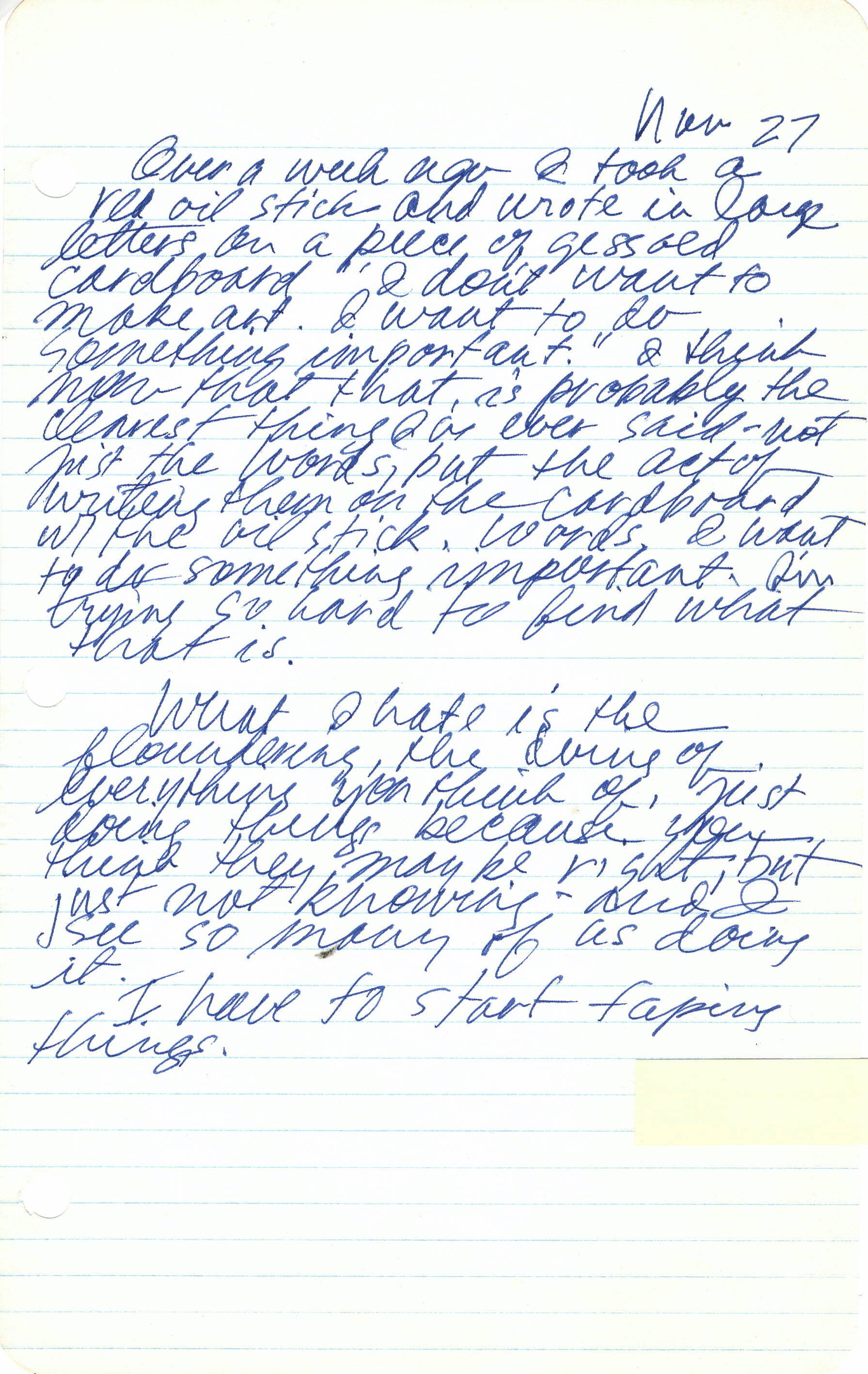

I’m writing now about the time between summer of 1979 and the middle of 1983 — roughly my two years at Miami University and my first 2 years in New York. This period of my life is the most heavily documented. (Well, that’s not strictly true — the late 90s and a few other random times are chronicled pretty extensively but for this particular project I’m stopping at, roughly, 1990.)

My high school diary is what sent me on this trail to begin with, and it contains some of the most compelling material for me, but it’s often very sketchy and selective regarding events. That’s typical of most of my journal-writing: much of it revolves around questions in my head, and people, places, and things are there sporadically but they are not the main thrust. All that is to say that my childhood and high school years are lightly documented and so were easier to write about because I was writing about memory, which is always accessible even if spotty and unreliable. But from the early 80s, I have piles of journals, drafts of plays and stories and essays, manuscripts, drawings, and various hybrids of all of the above. And whereas the years from 0-18 largely revolved around waiting, the following few years are dense with new experiences, exposure to new people and ideas, a massively hectic life in a city that never stops giving you something to do or contemplate, and men men men art art art. Things moved fast. It’s a lot to absorb and synthesize. Rabbit holes abound.

1982. I was 21. You know how it is.

Journal, 11/9/1980.

Poring over my journals and letters and manuscripts going back to when I was 14 has been — I guess not unexpectedly because why else would I be doing it? — revelatory in ways big and small. I think the most striking sort of overall discovery is that words I use now, habits of mind, views and opinions I hold deeply, things which I might have otherwise, without a lot of analysis, insisted I’d learned or developed over the course of 60 years, actually show up regularly and more or less fully-formed in my writing at 25, or 19, or 16.

This entry from 1980, when I was a sophomore at Miami University studying acting and directing, pulled me up short this morning. Not the first bit — that feeling of lostness is something I mention over and over in my journals from all ages. I mean the second paragraph, where I write that my closest friend and I are in the middle of a tense, painful episode, and even as it’s happening I’m mulling over its potential as “material.” It struck me as incredibly cold and also I recognize that I’m doing that all the time, every day.

It’s something I’ve heard lots of artists describe, that sense of there being two mental tracks running simultaneously all the time: one on which you experience your life, and two, the one where you’re observing and evaluating it as a “story.” But for some (obviously self-serving) reason I never really saw the stark reality that that process infiltrates every relationship I’ve ever had in my life. And I didn’t realize I was already so cold-blooded at 19.

Work these days consists mostly of poring over journals and correspondence, drawings, drafts, and manuscripts from the first half of the 1980s. And then feeling a bit nauseous and sad the rest of the day. Maybe the nausea is a side effect of the vaccine, I don’t know. But the sadness is not, not a medical side effect is what I mean, but I did start crying out of the blue on my walk home after I got the shot.

The big overall impression I get from this look back at my early twenties is how insanely precarious life was: practically and financially, artistically, emotionally and psychologically, physically. Jesus Christ. It’s just falling in love with every man who says hello, suicidal breakups, crazy druggy days and nights, losing jobs every other week and job hunting and quitting jobs and moving, and getting sick getting sick, making art and questioning it TO DEATH. And all that stuff is just the background for a wild life of incredible freedom and fun, ecstasy, abandon in a neighborhood that is vibrating with it all day every day.

Looking at all the ephemera from that time is disorienting and to say the least emotionally complicated. It’s a lot to process, but process I will! For my birthday, Chan gave me a week’s retreat in a cabin in the Adirondacks to write. Work here at home is going well and steadily, but it’ll be great to be alone with it for a chunk of time.

My reference to “an elegant line” is about one of my teachers at Parsons, where I studied fine arts — Harvey, whose last name I’ve forgotten — having said in a critique of one of my drawings that I had “an elegant line.” I was deeply insulted, shaken. I took it to mean that I was producing kitsch, not art, and from that moment on I was determined that all my lines would be inelegant. It’s like a phobia, back then and even still, my fear of being good enough at something to fake it. It was like every time I sat down to make art, of any kind, I had to reinvent the wheel. I couldn’t just paint, I had to invent painting first.

These journal entries are from the year after my year at Parsons. I had dropped out of school because I wanted to be an artist not an art student, but I was careening from one idea to the next, one style to another, a different medium every week or two, feeling like I’d figured it out, realizing I hadn’t, and over and over. (If I’d actually made every piece of conceptual art I described in my journal that fall, I’d … have made a lot of pieces of conceptual art.) I spent much of the previous fall sick, culminating in a bout of pneumonia, one shitty low-paying job after another, barely scraping by even in the cheap 80s East Village, and I was exhausted.

I was ideologically opposed to making money with my art. Not just a young idealistic desire to put artistic before commercial considerations, but a moral line in the sand. And yet I complained constantly about having to do other work to pay the bills. I don’t remember seeing the dilemma built into that.

These years were consequential years. I began to get a sense of myself as an artist, what was important, what was not, and I fell deeply in love about 25 times, mostly with men I’d spent one night with and never saw again and then I fell in love for real and it nearly killed me.

(The period of 1982-84, at least as I’m mapping it out now, will be the climax of my book, when all the threads come together: my first serious love and heartbreak, the arrest and trial for child molestation in my hometown of the man with whom I had my first sexual experience at 16, and the active years of the serial killer Larry Eyler in and around that part of Indiana.)

So … I will be 60 on Monday. I have reached that age “when the real anxiety comes, about the passing of time, about age and death and accomplishment, when I can’t say ‘I’m young’ anymore.” I want to go back and tell my 21-year-old self that he’s right to be vigilant about the elegant line. And also, calm the fuck down man.

(Probably don’t read this if you plan to watch the series. If you haven’t seen it, do. It’s gripping.)

I’ve seen lots of rapturous reviews of It’s A Sin in social media, and I’ve seen some very strong criticism. It’s unavoidable that a series whose subject is the AIDS plague years would arouse strong feelings and opinions among the men and women who lived through those years in those communities.

Most of the negative critique seems to center around the scene near the end, after the death of Ritchie, who, in the first episode fled his homophobic family to come to London (all the characters do that) and who early on dismissed the seriousness of the risk of getting infected and the risk of infecting others. The scene is between Ritchie’s mother and his best girlfriend, Jill. Jill says:

“Actually, it is your fault, Mrs. Tozer — all of this is your fault… Right from the start. I don’t know what happened to you, to make that house so loveless, that’s why Ritchie grew up so ashamed of himself — and then he killed people! He was ashamed, he kept on being ashamed, he kept shame going by having sex with men, infecting them, and then running away. Cuz that’s what shame does, Valerie, it makes him think he deserves it. The wards are full of men who think they deserve it. They are dying, and a little bit of them thinks ‘Yes, this is right, I brought this on myself, it’s my fault because the sex that I love is killing me.’“

The monologue is a gut punch when you’ve spent your life arguing that promiscuity was not killing us, sex was not killing us, we were not killing ourselves. Governmental neglect and societal indifference and antipathy were killing us.

A common slogan on posters and other ACT UP media was “Homophobia kills.” Meaning that a homophobic government was ignoring the pandemic because it was queers who were dying. A homophobic society didn’t care that we were dying, because it was our own fault, and we deserved it. But this series asserts something deeper and more insidious: homophobia causes gay men to feel shame, and shame makes them hate themselves, which causes them to believe their lives are worthless. They internalize society’s view of them, and that causes their promiscuity and carelessness about sex. That’s a lot to swallow when you have cut your gay political teeth on the idea that openly celebrating our sexuality is the most potent political weapon we can exercise, the most important act of resistance.

(And of course there’s a convincing argument to be made that the conservative turn of the post-90s gay rights movement, toward marriage, children, military service, assimilation, and away from sexual freedom is a community-wide shame reaction to the plague years. It’s A Sin is very much a post-90s work of art, a product of this era.)

Here’s what I think. Can we allow for the possibility that we experience, and perceive, our promiscuity as both things: freedom, joy, celebration and a grinding compulsive need to replace our self-hatred, even if it’s just for a few minutes, with the feeling of worth and control that being attractive to someone brings? For me, in my life, promiscuity was both these things at different times and often at the same time.

Pride and shame are two sides of the same coin. Can anyone honestly say that when they came out all the bad feelings just went “poof!” For me, coming out, being out, feeling pride, protesting homophobia, all these things are part of a lifelong project to chip away at the shame. We insist on joy because we’ve been told all our lives that our desire is disgusting. We live in a world that hates us. That was true when I was a child, true in 1979 when I came out, true in 1981, and it’s still true. How would we not feel shame?

I think depicting gay men who don’t feel shame, who don’t to some extent think terrible things about themselves, hate themselves sometimes, would be a misrepresentation, but as a community we do it all the time, refuse to acknowledge our shame, our damage, our pain. The relentless rainbows and unicorns PRIDE! message might be politically necessary, but it can compound our shame. Constantly being told that we should be proud and not ashamed makes us ashamed of our shame.

My thoughts, for what they’re worth.

One thing I can’t really make sense of is that this monologue, this “thesis statement,” comes not from one of the gay men characters — who would presumably speak with more authority on the subject — but from the straight woman friend. To be honest, I’m not sure how to parse that narrative choice.

This is one of a set of snapshots of my mother and father’s wedding in the summer of 1958. I think Mom said that it was a photo of the wedding day lunch, which maybe was a more traditional affair than it is now, or possibly more traditional there than it is everywhere? I don’t know. It was taken in the kitchen of the DeMeyer farmhouse on Grange Hall Road in Gurnee, Illinois. The road is now much bigger and busier and has a different name, and the house, though still standing, has been converted into municipal offices and is unrecognizable. I don’t know how this photo was separated from the set, but I ended up with it in my 20s. I loved it and probably just asked to have it.

When I left Brian in 1990, I moved from our apartment on Ashland in Ft. Greene to an apartment on Warren Street in Boerum Hill on the other side of Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. I had never lived alone in New York but I had just negotiated a large raise in my hourly rate as a temp proofreader, and I could afford the tiny one-bedroom apartment in what was then a very poor neighborhood. The apartment was on the top floor of a row house, freshly painted, no frills but clean. My landlord was only a little older than me, had long wavy hair, muscles, and crooked teeth, and coming and going I often saw him cleaning or repairing the building and another building he owned nearby. He wore very short black leather shorts and a cropped tight white t-shirt when he worked outside.

The outside wall of my long, narrow kitchen was exposed brick. Next to a small table where I ate my meals, I hung several small framed photographs and pieces of art that were special to me so I could look at them while I ate, this photo among them.

Days after I signed the lease, my graveyard shift “perma-temp” gig at Weil Gotshal collapsed with everything else that collapsed at the end of the 80s, and I could no longer afford the rent. Luckily, my old friend Joan needed a roommate in her apartment on 10th and 1st — I had lived there with Joan years earlier, when I was at Parsons — so I broke my lease in Brooklyn and moved back to the East Village.

When I took down the art from the brick wall, the frame on this photo felt damp in the back, and then I saw that the wall itself was wet, possibly with condensation or maybe the brick wasn’t sealed so moisture came through the wall when it rained. Water had seeped into the frame, behind the glass, and when I tried to remove the photo, no matter how carefully or slowly I worked, most of its surface came off with the glass.

On the left you can see Diane, one of my mother’s best girlfriends in high school, who was a bridesmaid, with her husband at the time. In the left foreground is probably Don, my mother’s little brother and next to him would be Mom’s much younger sister, Nicki, who was called Susan then. If you look closely you can see Mom at the head of the table, framed by the window, and farther right the front of my grandmother Elsie’s face, and then at the far right a fragment of my mother’s best friend and maid of honor, Carole. On the table are what look like a platter of fried chicken and a plate of large rolls. The table is set with what were their best dishes, probably my grandparents’ wedding China. It could just be the awkwardness of being caught off guard for a snapshot, or the stiffness of the formal clothes and serious occasion, but no one looks comfortable, no one is smiling in this photo. All of these things were of course much clearer to see before the photo was damaged.

This is the only photo I know of taken inside that house. I feel sick to my stomach every time I see it, contemplating the loss. But Mom never shared good memories associated with that house; she only talked about violent arguments and days-long bitter silences between my grandmother Elsie and grandfather Emil DeMeyer. And between Emil and my mother’s older sister Carol. It was not a happy family.

Pretty sure all my friends have heard me go on about my grandfather Edward Cheslik, who my father believes was a homosexual and who was certainly an alcoholic and an unreliable husband and father, as far as that goes. My father told me these things when I came out to my parents at 20 (if you accept my telling) or 18 (if you believe my mother). And when I say “told me” that’s short for “told my mother and she told me.”

This story, or these stories, or I should say the gaps in this story, are, I’m realizing, the driving force of my life’s work. In my twenties, I wrote a song called My Family Tree, the subject of which was not knowing anything about the man my grandfather loved. (My father has since changed the way he tells it — he used to say that his father disappeared several times, his mother tracked him down, and she always found him living with a particular man, but recently Dad told me that it was not the same man but always a different man. Though there’s no way to be sure, I’m inclined to go with the first version because my father often alters facts in stories in later tellings. But to be sure it is possible the revision is correct.)

The geography of my father’s childhood tracks his abandonment by his father. Lenore found Ed in Albert Lea, she packed up and moved the family to Albert Lea. Lenore found Ed in Waukegan, she packed up the family and moved to Waukegan — where my father met my mother and where I was born. Even a series of earlier moves within Winona, where they lived when my dad was little and where the Chesliks go back several generations, seem to have been prompted by a series of frustratingly undescribed “scandals.”

For a long time, that was enough to know. Or I should say it was enough to not know. Just the knowledge that my grandfather was probably queer, the sense of a forebear, was potent and moving to me. More recently I’m less satisfied. As I’ve studied more and more lives of gay people and seen how almost every biography is full of holes — holes created specifically, explicitly, by the imperative to preserve secrecy in order to avoid public shame, ostracization, injury, death: correspondence burned, personal papers burned, everything containing any hint of intimate or domestic life, any sign of love, destroyed, lost to history — I’ve become more angry, more unsettled, more heartbroken. Because it’s not just a family history lost but the history of a people.

I mean to tell Edward’s story in this book I’m writing, and I want more to tell.

My grandfather and my grandmother Lenore were divorced I think in the very late 1950s or early 1960s. My mother said that Ed held me as a baby, and then, after many shorter disappearances, disappeared for good. In 1965, he was found dead under a tractor trailer in Tucson where he had crawled for warmth and shelter. He was what they used to call a “transient” — homeless. He must have been carrying identification because the small article in the Arizona Daily Star about his death named him, and the coroner phoned his “next of kin,” his sister Sylvia in Minnesota. Silvia flew, alone, to Arizona to identify and claim the body of her brother. She and the minister were the only people at the funeral service. Edward Paul Cheslik was buried in Holy Hope Cemetery in Tucson.

Now I yearn for the seemingly impossible. Who was the man he left his family to be with? Or was it men? Where did they meet, and how? What could it possibly have been like to be a homosexual in small town Minnesota in the 1920s? 1930s? Where was Ed during the period after his final disappearance until his death a few years later? There are 1800 highway miles between Waukegan, Illinois and Tucson, Arizona. Why Tucson? Where did he stop along the way? For how long? How did he get by?

I found a woman on Ancestry.com, in that list they give you of “2nd/3rd cousin, shared DNA,” who had written a short remembrance of her grandmother Silvia Cheslik Luxem, Ed’s sister. I sent her a note asking if she had heard any family stories of Ed. She wrote back right away, having contacted an aunt who was Silvia’s daughter. The aunt remembered Ed and Lenore and that Ed had disappeared and the family never spoke of it, and she remembered meeting my father when he was a teenager and he showed her his model airplanes. Just reading these fragments of a stranger’s memory of my father and his family this morning I found myself suddenly crying, though it amounts to nothing much.

Most people research their genealogies, construct their family trees, based on marriage records, but of course there’s none of that. I know about Ed’s marriage, but that’s such a small part of his story. Maybe one of the big questions I need to answer as I write this book is — what is the nature of a story that has been mostly erased, the only people who might have had direct memories of it all dead, about a man whose family for the most part wanted to forget and nobody living much cares about?

I just want to give Edward Cheslik’s life the dignity of being remembered, and I don’t know how to do that.

We’re three days into the Little Drummer Boy Challenge and Whamageddon (so far, so good) which I think really just stand in for our collective impulse to run from all the the terrible Christmas songs and execrable recordings of good Christmas songs that saturate our manmade environment for 6 weeks every year — though this year most of us are getting a break from it because we’re not leaving home. OR SHOULDN’T BE.

I don’t have any strong feelings about the Wham! song. It’s fluff and doesn’t pretend to be anything but. I don’t mind it nearly as much as, I don’t know, Christine Aguilera bushwhacking her way through O Holy Night. The LDBC I take much more seriously. There literally is no song worse than that song, and there are a thousand self-serious covers of it out there, from Boyz II Men to Bad Religion, waiting to assault you. It is endless and, for such a messagey song, it has no message. I hate it.

I do have strong feelings about Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas, and I avoid it more scrupulously than either of the official challenge songs because the revised version that everyone sings now completely misses, or I should say avoids, the whole point of the song, which is the whole point of the season, which is that, no matter how bad things might be right now, if you have faith, the darkness will end. There will be light again. You don’t have to be Christian or even religious to feel the power of that metaphor.

Reportedly, Frank Sinatra loved the song but didn’t want to sing something so sad — the obvious question being that if he loved the song why did he murder it? — and had it re-written. (It’s fitting that Sinatra is the culprit here. Much later, he stole New York, New York from Liza Minelli, who, also, like her mom, did it better. To say the least.)

I was heartened to come across this article this morning. Maybe this year, because the words of the song, as in its original wartime context, can be read absolutely literally, it’s possible to appreciate again the power of this song, its honesty about our sorrowful circumstances, the pain we feel being so long separated from so many of our loved ones, a pain without which the hope in the song (“someday soon we all will be together”), the faith, the promise of light after the long dark night has no meaning.

It is, no question, the best Christmas song ever written. But you will never hear it even if you spend from now to Christmas Eve in a mall. You will hear some bullshit that sounds like it about a million times. If you want, you can do what I do: every time someone starts singing it, sing along (either out loud or in your head — read the room) but sing the original lyrics.

I found another journal!

There have been huge gaps, sometimes of many years, in my journal-keeping, particularly frustrating because they often occur at times when the most is going on in my life. But this one is a real find — a lot is happening.

Armelia McQueen died today (or yesterday?), which sent me looking for the Playbills that I saved from my first trip to New York in 1979. The second Broadway show I saw was Ain’t Misbehavin’. For years, decades, I used to tell people that I’d seen the original cast with Nell Carter, and I truly believed that I had, but several years ago I was looking at the Playbill I’d saved and I realized that I’d seen a replacement cast over a year after the show had opened. So … I love Armelia McQueen, my college friends and I wore that cast album out so I’m very familiar with her voice, but I wanted to see if by chance she was still in the Broadway production when I saw it. She was not.

But as I was digging, I found a stack of pages tied with a shoelace, and it turned out to be my journal from spring of 1982 to June 1983, for some reason stored separately from the other journals. It’s the period of time when I’m becoming more and more impatient with studying fine arts at Parsons, contemplating and then deciding to leave school and just be an artist in the city.

I spent that summer back in Greencastle, Indiana, working at a menial job on the graveyard shift at IBM and living cheap to save up a little cushion (back then, $100 was a sizable cushion). But before that, in Indiana for Christmas, I met this guy Paul. I don’t remember a lot about him, except that he was visiting my friend Nancy, that the night we met we played footsy under the table at dinner or a bar where we’d gone out with a group of friends, that he was very handsome, and I think a music student, and that I was obsessed with him for a disproportionate length of time considering we saw each other twice.

We slept together that night, and I fell deep into a crazy obsession, which was par for the course for me back then. That was before I learned that lust and love are two different things. He gave me crabs, which took a while to get rid of. Then, I saw him again that spring, and he gave me crabs again! As far as I remember I didn’t see him again.

I don’t remember any of the stuff I’ve written here about Chicago. Scott was my best friend in college, and I don’t think he even knew Paul.

His last name was unusual enough that I found him quickly with a Google search. He worked as an actor for many years in Chicago and Los Angeles. At some point, he met a man and together they started a successful catering company. He died of AIDS in 1995.

I mean I know those years actually happened (though as I read my journal from that period I would say a good half of the gigs I mention I have no recollection of) but I don’t know how we did it, day after day after day. Man were we busy. A couple weeks before this entry, one of our cats had died, another was on death’s door with a failing liver, we were in the middle of the process of pitching a variety show to execs at Comedy Central, preparing to move to Nashville, and we were playing several shows a week, most of them out of town, while still working full-time at a law firm.

That period of time felt very much like the beginning of something big, but it was, looking back, the beginning of the end.

Four years later, after it really did end, therapy and meditation and a lot of hard core self-examination helped me reconnect with my love of the work and loosen my intense attachment to the idea that it must lead to fame and fortune. Every once in a while in the last 10 years or so, the various successes of LIzZie will arouse that old familiar feeling of inevitability, that you just have to bear down harder and harder and it will happen. It’s not true, it’s not productive, and it eventually destroys the work, so I have my guard up against its return. But now, reading this and being reminded just how extreme that feeling was back then, how it controlled every aspect of our lives, I realize I don’t have to worry. I will never be that crazy again, it would kill me, not just the cats.

My intention recently is to focus on my work to divert my mind from election news. Obviously, I don't always succeed, but I have managed to stick with it for at least a few hours every day for the last few weeks

The work right now consists mostly of reading my old journals. The last few days it's the period (late 1997 - spring 1999) when Jay and I were floundering in New York and moved to Nashville, which was a time of grinding uncertainty about the future, low lows and high highs. My journals are dense with anxiety about the direction of our career, endless speculation and hypothetical scenarios, picking apart every decision, every plan, every dream and aspiration. So the reading is every bit as emotionally taxing as the news. At least it is productive.

One thing we did during that time was rent an RV and take a road trip to Austin for SXSW. We took along two people, Suzanne, our neighbor and dear friend who performed with us many times and often took care of our four cats when we were away. And our friend Brian, who was a student at the time, a filmmaker and lighting designer who did lights for our shows at HERE. And we took all four cats with us. (That’s Honey on my lap in the photo.)

The trip was magical and joyful and weird and a lot of fun. (On the other hand, SXSW itself was mostly kind of awful — ah, those lows and highs.) Brian shot lots of video and made a film. This clip is from the drive down when we stopped at Suzanne’s parents’ home in Charlottesville for a night. A couple minutes in, there’s a bit of us singing one of my favorite songs we ever sang, “Far Side Banks of Jordan.” Terry Smith wrote the song, but Johnny and June made it famous. Sorry for the poor quality video, it’s from a very old VHS.

I don’t miss those days at all. But I miss those days.