For National Coming Out Day today, here’s an excerpt from the book I’m writing:

❦

I didn’t, that I know of, meet my cousin Lucretia until I was eleven or twelve. I grew up thinking of her as my only first cousin, the daughter of my father’s late sister, Jane. My mother’s sisters both had children but they lived in California and we never saw them. The only cousin we knew as young kids was my mother’s first cousin, Cathy, who was close to my brother’s age -- Mom’s Aunt Alice had her last child when she was in her forties.

Jane, four years older than Dad, married a cocky young lawyer, John, in 1949, had one child, Lucretia, and died in 1959 of a blood infection after a hospital stay that lasted eight months in the middle of which my mother and father got married. Jane was in law school when she became ill. Lucretia was three years old when her mother died. John remarried quickly to a woman named Janice who bore five sons before they divorced. By the time I met John years later, he was a prominent judge in St. Paul and married to his third wife, Judy. After Christmas of my freshman year of high school, Michael and I took the bus with Grandma Lenore from Greencastle back to St. Paul to spend a week with the Kirbys in a Minnesota winter so cold the insides of my nostrils turned to ice when I breathed. Trailways took us as far as Chicago where we ran for blocks through snow and near-zero temperatures through downtown Chicago in the dark to the Greyhound station. The station was bright and cold and full of people sleeping on benches. Grandma admonished us firmly not to use the restrooms without telling her, and when our bus to St. Paul arrived, she grabbed her luggage and our arms, ran to the gate, and pushed herself and Michael and me into the front of the line of dozens of people who’d been standing there waiting for who knows how long.

Lu, who was five or six years older than us, introduced us to snowmobiling and tequila, and took us to a party where we smoked marijuana for the first time, sitting in a circle in someone’s basement passing a joint, the whole crowd chanting “Hold it! Hold it!” after I inhaled. I worshiped my cousin Lu.

I don’t remember why or how or even exactly when, but Lu started spending Christmases with our family. The first time I remember, which might have been the first time, she was on her way home from a student trip to England and she brought souvenir candy from Stratford-on-Avon, a bag of “scone mix,” and the Iron Butterfly record, In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida. She brought gifts for everyone, incense and Chinese brass incense burners for me and Michael, the smell of which made me nauseous for several days but I didn’t tell a soul. All of it was exotic and cosmopolitan for Indiana in the early 1970s, even the three-year-old Iron Butterfly album, even Lu, tall and broad-shouldered with long brown hair (that she told us she ironed), dressed plainly in jeans and a sweater. She spoke in a direct, forthright tone of voice, and she read Herman Hesse and Ayn Rand. She wrote poetry. My father said she had “class,” his highest compliment, a word that to him meant educated, worldly, sophisticated: everything that Indiana could never be. Grandma Lenore shook her head and lamented Lu’s “long stride.”

The year following that trip to Minnesota, Lu’s Christmas gift to me was a book of blank white pages; its dust cover read, “The Nothing Book: Wanna Make Something Of It?”. In the center of the first page, I carefully inscribed, “A Collection of Thoughts” and on the next page:

December 27, 1976

Since this was an “indirect” gift from my cousin, I will start out with one of my thoughts while talking with her and then go into some of her thoughts. This is one of my “verbally expressed” thoughts.

“If people can’t take me for what I am, then I don’t want them to take me at all.”

A few pages later I transcribed one of Lu’s poems:

Young man with your quick

ready hand.

Sketching flashes of life,

That too often move by …

missing my glance.

You stop them in an instant.

Freeze them with your hand.

I look very quickly but …

You’ve ingrained them in

my mind.

Then a little Lord Byron, Langston Hughes, a fragment of lyrics from Seasons in the Sun which had been a big AM radio hit a year or two back, a handful of unattributed proverbs in the tradition of Grandma Lenore’s scrapbooks, but by January 7, I was chafing against the format, moved to express feelings more directly — on Tamara Burkett’s Dear John letter (I gave her a houseplant for Christmas, she gave me a concise handwritten note telling me that she liked me but not enough): “I wish she had a reason -- that girl’s got real hang-ups such a shallow personality at least we don’t hate each other -- I hate it when it ends that way.”

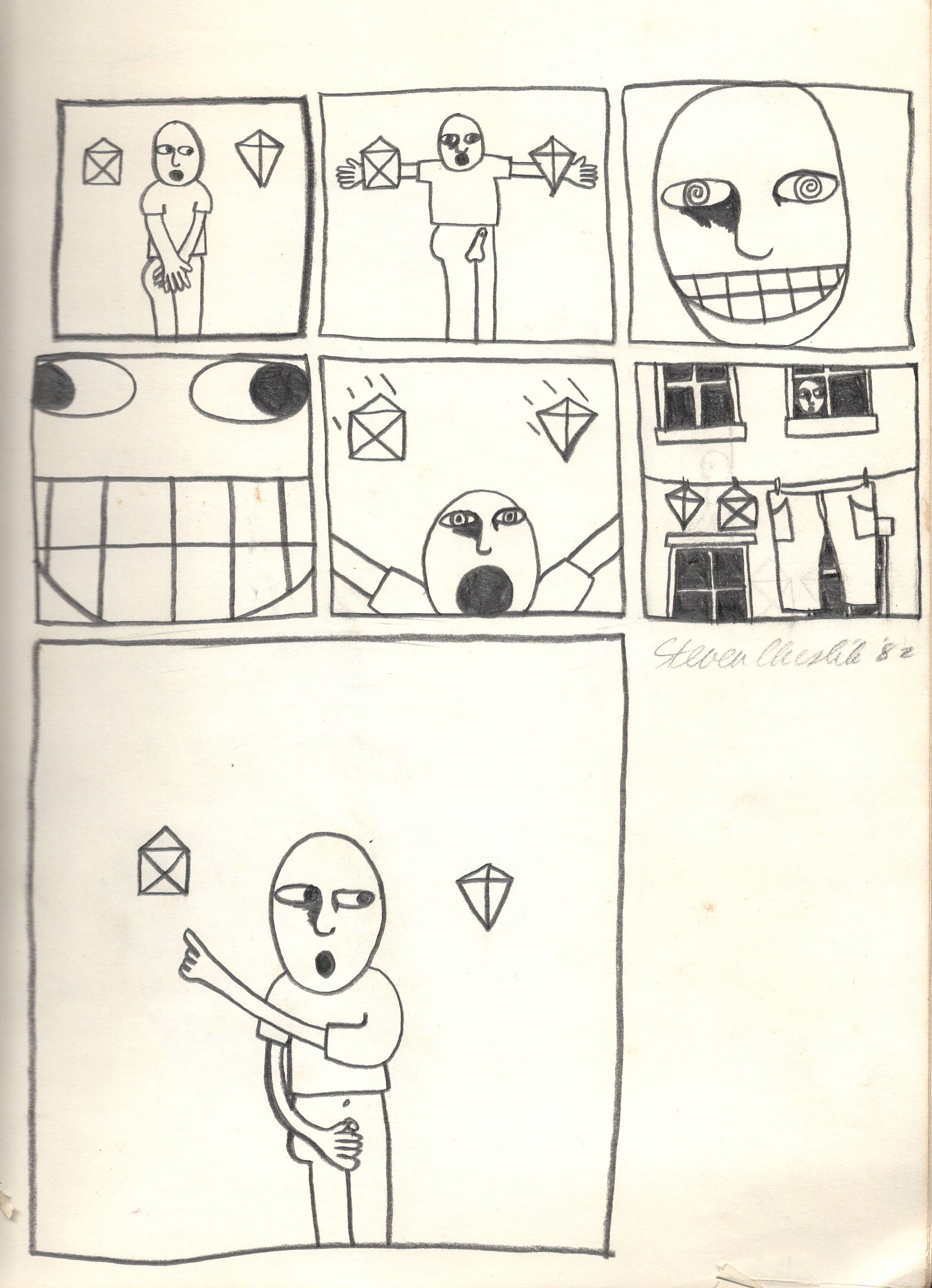

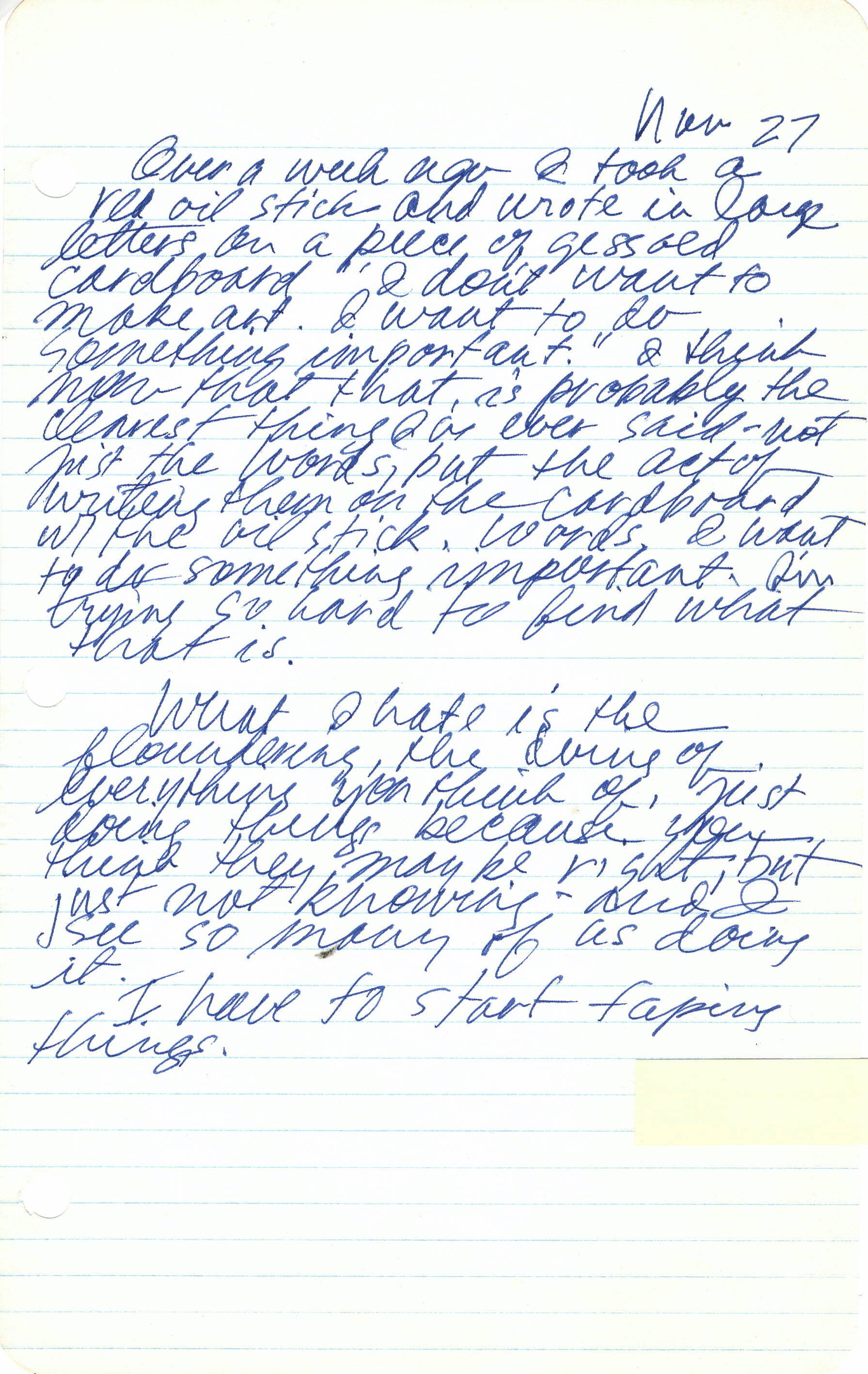

And I started keeping a regular diary. The Nothing Book became my founding document, nearly scriptural, the physical object, with its crumbling dust jacket, a phylactery. I became an artist in its pages, admitted to myself that I was a homosexual, panicked and cut the pages out with an Exacto knife and burned them, then, weeks later, braver, came out again, scribbling pages and pages of bottled-up sexual fantasies about the boys and teachers at school. Everything important that I believe and desire, the moral principles that guide me still, my feelings about love, everything I yearn for, all had their first utterance in that book that I wrote in from Christmas of 1976 to the end of my junior year of high school.