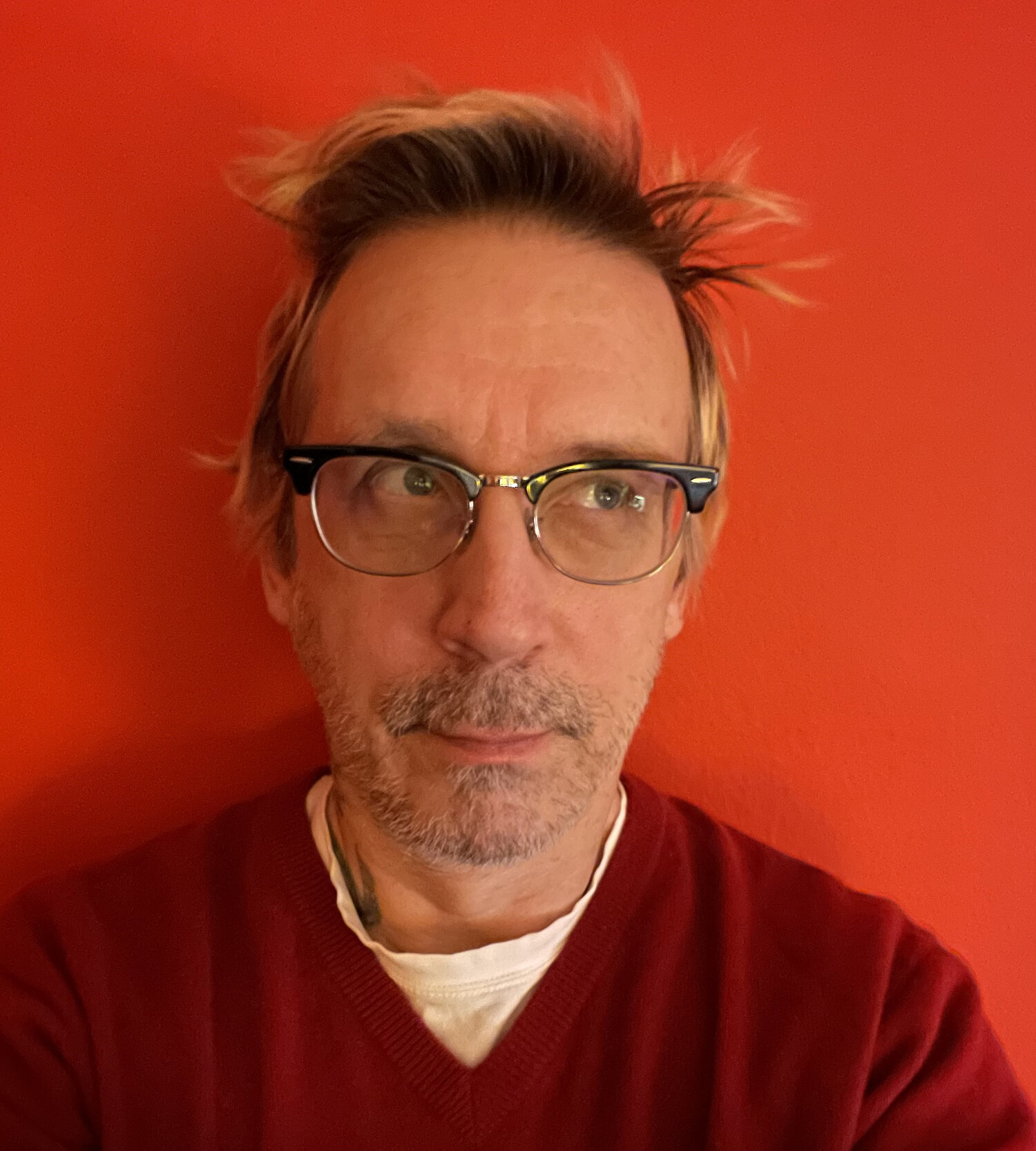

Somebody Did Something.

My LIZZIE co-writers and I are doing some housekeeping this week to get performance royalties for the LIZZIE studio album squared away. It’s all work we should have done years ago, but it’s tedious and we’ve put it off. Besides, right now the potential royalties are very small because hardly any radio or TV stations are playing the record, but it’s the kind of thing that, at some point and you can’t predict when, could be real revenue.

Which means we have to, for each song, assign percentages to each writer’s contribution. Some of these are easy. Alan wrote This Is Not Love. I wrote Why Are All These Heads Off? But then there are songs like Burn The Old Thing Up, which started as lyrics Tim wrote and handed to me. I set them to music, revising them to fit. A dozen years later, when Alan joined us he pulled apart the song and put it back together.

For songs like that, as well as many of the newer songs that we all wrote together, it was a matter of recalling memories, digging out old demos, searching emails, to recreate the process and arrive at a split that seems fair and accurate.

Part of me hates this because I so love how when you make theater everyone’s contributions send tendrils into everyone else’s and it’s often impossible in the end to see the work as anything but an organic whole. But what I have enjoyed is looking back at older versions of LIZZIE (nee Lizzie Borden). Because it’s been around a while, not just as a musical in development but as an experimental devised performance which gradually over 25 years turned into a rock opera. And WE did that.

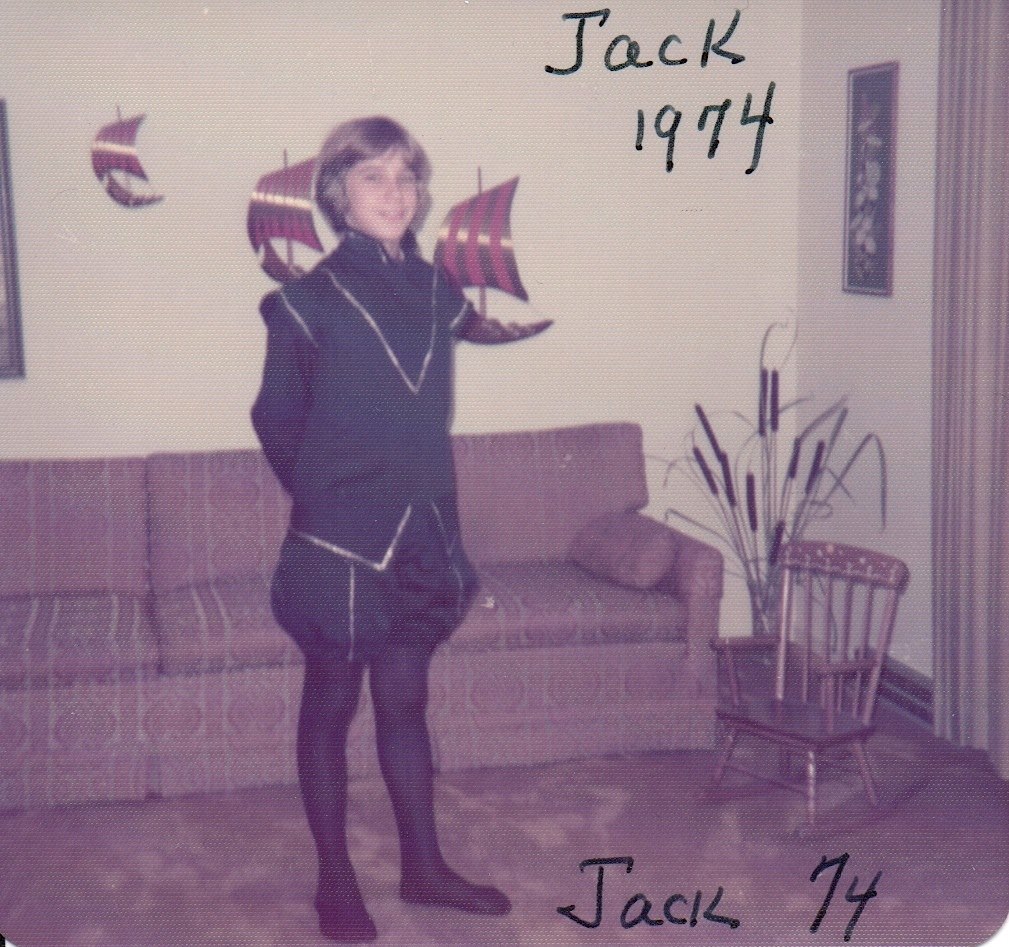

One of the things I dug up is a video of the 1994 production at HERE Arts Center. I hadn’t seen it, didn’t know it existed. It was on a DVD with “Lizzie Borden” written on it in Tim’s scrawl in black Sharpie. As I wrote to Alan yesterday, “despite how Tim and I always say that we weren't interested in telling the story to the audience back then, I see that there IS a story, an emotional arc, it's just a very different kind of storytelling, cryptic, poetic, sensual. We decided later to make it literal, explicit. I love that this piece has been so rich as to be able to be both those things, and that that earlier thing, whatever it was, is still immanent in the new version.”

It affected me deeply watching the video, not just to get a glimpse of our younger selves, our raw energy, our potential, but witnessing again the power this piece had then to move audiences and move us — we really knew even then that it was special — and then seeing in such concrete terms the hugeness of the work the three of us have done together in the intervening years to create what we have now.

So here is a short clip. This is Somebody Will Do Something, like it was in 1994: